|

|

A

Brief History of the English Language

The

English language is the child of a marriage between two very

different languages-a kind of German (Anglo-Saxon) and a

kind of Latin (French). Three fourths of the words we use

all the time are Germanic, but new words come from the

classical languages. Anglo-Saxon is a dead language that

stayed dead; Latin and Greek remain alive because we use

their pieces (like philo-) to form new words. Learn a

little about these languages, and those long words that look

so look so intimidating will break apart into delicious

little crumbs.

|

|

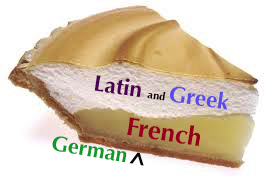

The

English language has passed through three major phases,

roughly layered like a lemon meringue pie:

Short

Germanic words make up the crust. Above the crust, creamy

French words make a delightful filling, and the whole is

topped by an immense foamy meringue, the Greek and Latin

words that got fixed in the language during the Renaissance.

|

|

Germanic

words came in with the Angles and Saxons (and Jutes), who

overran England in 449, defeating the legendary King Arthur and

his Celts. Gritty and necessary, these words form the crust

underneath the linguistic pie. The common words of English are

Germanic-perhaps 80% of the words we use all the time. This

group contains words for actual things in the real world (e.g.,

house, earth, man, pig) and the words that glue sentences

together (e.g., prepositions, conjunctions, pronouns,

demonstratives, and four-letter words).

In

1066 William the Conqueror and his Norman French forces took

over England in 1066. This resulted in the layering of

languages.

Above

the crust, the French words, longer and more melodious, gel

into a creamy filling. These words are blurred Latin: you can

see the familiar features of Latin words, but whole syllables

have dropped off or single vowels have spread into double

vowels. (See Latinate and Germanic words). For a while, two

social groups, the rulers and the ruled, spoke two separate

languages. The upper classes spoke French; the peasants spoke

Anglo-Saxon.

Anglo-Saxon

and French were spoken side by side until the fourteenth

century, when they coalesced to form English. The two language

layers remained distinct, however, retaining their connotations

of nature and culture. Nature and culture are perfectly opposed

in the contrasting vocabularies, one Germanic, the other a

hybrid of Latin and German: the gritty crust and the creamy

filling.

In

Ivanhoe,

Sir Walter Scott pointed out that the English words for an

animal and the meat of an animal come from two linguistic

groups. The French lord demanded an animal-cow, sheep, pig-in

French: boeuf, mouton, porc. The French words eventually became

the English words, beef, mutton, and pork. No other language

distinguishes between the animal and its meat. English makes

this distinction because Anglo-Saxon-speaking peasants raised

the animals eaten by the French-speaking aristocrats. The

Germanic word names the animal in its natural state, while the

French word denotes the animal's flesh, improved by art in a

delicious sauce.

The

foamy topping sits like a meringue, a huge, fluffy layer of

foamy Latin and Greek words. For a long time, Latin was the

language chosen by ambitious writers who wanted international

readers and immortal fame. They knew that languages such as

Anglo-Saxon changed and died. Latin, being dead, could not

change, and so it became the language of immortality. Even

after writers trusted their own languages enough to write in

them, scholars continued to write scientific, religious, and

legal treatises in Latin. When they turned their treatises into

English, they naturally reached for the Latin words they grew

up with and which easily turned into long English ones. During

the Renaissance, Latinate words poured into English. With them

came words from Greek. After the capture of Constantinople (now

named Istanbul) by the Turks in 1453, scholars fled clutching

their Greek manuscripts to Europe. Latin had always been

around. It had been the language of the church, of law, of

diplomacy, of science. Greek had been lost for hundreds of

years. Latin words had status, Greek words had prestige.

Over

the centuries, words from Greek and Latin entered professional

vocabulary, which we still see today in medical, legal, and

literary jargon. Specialized words warn off outsiders. Doctors

put patients in their place by choosing the technical word,

hypoxia, instead of "low oxygen," which anybody can

understand. Academic writers, especially, affect a Latinate

diction. "Look," the words seem to declare, "The writer

is smart!" They obscure the ideas and, too often, the absence

of ideas.

|